WHAT IS HLH?

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a hyperinflammatory syndrome resulting in life-threatening organ damage. 'Hyperinflammation' means that the immune system is turned on far more intensely than it ever should be.

This is different than 'autoimmune,' which refers to the immune system being misdirected. HLH is characterized by a unique set of clinical and laboratory features such as low blood counts, very elevated markers of inflammation, and an increase in the size of the spleen. This distinctive condition occurs in different clinical contexts, where it may appear and be treated somewhat differently.

HEMO · PHAGO · CYTIC

LYMPHO · HISTIO · CYT · OSIS

'HEMO' stands for blood

'PHAGO' refers to 'eating'

'LYMPHO' refers to lymphocytes, important cells of the immune system that direct the fight

'HISTIO' (or histiocyte) refers to macrophages, which are immune cells that often engulf invaders

'OSIS' means too much or too many

When you put it all together, it literally means 'blood eating condition with too many immune cells.'

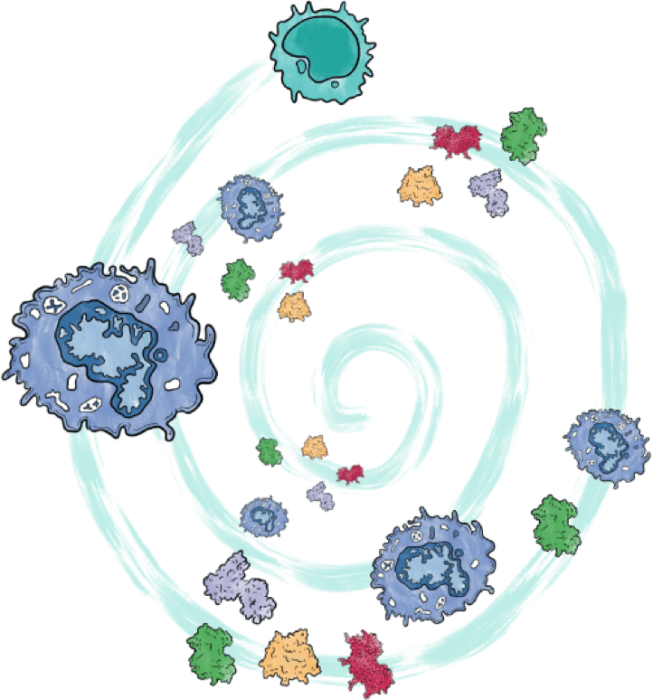

In HLH, the immune system is trying too hard to defend the body. But, ironically, it hurts the body in various ways because it is 'hyperactivated.'

An important part of this hyperactivation is the excessive release of inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines are messenger proteins that communicate between cells to drive the body's response to illness. An uncontrolled excess of cytokines is often called a 'cytokine storm', though this term also applies to conditions other than HLH.

In individuals with familial HLH, inherited genetic abnormalities damage a key 'off switch' in the immune system, such that it struggles to turn off, and cytokine storm develops.

What are the signs and symptoms of HLH?

Individuals with HLH usually have fever, low blood counts, enlarged spleen, and very high markers of inflammation. The process may also affect the brain and the liver, causing seizures and neurologic problems, or jaundice and serious liver injury. Additional medical complications may also develop. Though clinical features vary in severity from patient-to-patient, common signs and symptoms include:

FEVER

HLH is characterized by persistent fever. Usually, other, more common causes of fever such as infections will be ruled out.

LOW BLOOD COUNTS

Patients with HLH often have decreased blood counts, due to macrophages attacking blood cells. This can lead to:

- Low neutrophil counts (neutropenia): May lead to increased risk of bacterial or fungal infections

- Low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia): May lead to increased risk of bleeding

- Low red blood cell counts (anemia): May lead to fatigue and/or shortness of breath

ENLARGED SPLEENS

Patients with HLH often have enlarged spleens causing abdominal swelling.

NEUROLOGICAL SYMPTOMS

A wide variety of central nervous system symptoms can occur:

- Seizures

- Fatigue

- A decreased or an increased muscle tone

- Coordination disturbances

- Nerve weakness

- Paralysis and coma (rare)

Some patients with HLH may experience additional symptoms including jaundice, skin rash, and bleeding problems. However, some patients with HLH may lack apparent symptoms for a long time. Early diagnosis of HLH allows treatment prior to the development of irreversible complications.

What causes HLH?

GENETICS

HLH is most commonly caused by inherited genetic abnormalities. Patients with genetic problems leading to HLH are usually infants or young children. Even when the underlying cause of HLH is a genetic problem that creates an abnormal immune system, HLH is often (but not always) triggered by viruses or other infections that start the inflammatory process (e.g., Epstein Barr virus). As HLH is the result of genetic factors interacting with environmental ones, more severe genetic abnormalities typically cause HLH to occur at younger ages with milder triggers. Genetic defects affecting the protein perforin were the first to be discovered in association with HLH and helped us learn the disease's mechanism. These alterations interfere with a process that is supposed to terminate the immune response, leading to persistent activation of immune cells called T cells, which activate macrophages. Common genes associated with HLH include PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, STXBP2, RAB27A, LYST, SH2D1A, XIAP, and NLRC4.

In many patients with HLH, the genetic cause has not yet been identified. However, with the help of registry participants, the INTO-HLH Registry can potentially identify new genes and better characterize known genes causing HLH.

RHEUMATOLOGIC DISEASES/MACROPHAGE ACTIVATING SYNDROME

HLH can occur in individuals with rheumatologic diseases, especially systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), where it is typically called 'Macrophage Activation Syndrome' (MAS). HLH/MAS often starts with fever and rash, and it can be the first manifestation of the rheumatologic disease or a symptom of an existing one. The prognosis of these patients is better than other subtypes, with 90% or more of the patients alive after five years of the disease's first presentation. These patients are usually treated differently from patients with familial HLH and have specific complications to their disease, including a unique form of lung disease. Most of these patients do not require bone marrow transplantation for treatment.

The INTO-HLH Registry will gather data to understand how to best treat these patients to avoid toxicities and keep inflammation under control.

CANCER

Cancer, specifically cancer affecting blood cells, is the most common trigger associated with HLH in adult patients. Unfortunately, these patients have the worst prognosis of all HLH subtypes, with only 10-30% of the patients surviving after five years from the HLH episode. HLH is presumed to occur in 1% of patients with hematologic malignancies. It is higher in lymphoma patients- around 3% of all patients with lymphoma and up to 20% in lymphoma types that are more associated with the syndrome (such as T cell/Histiocyte rich B cell lymphoma).

The mechanism and appropriate treatment for patients with cancer and HLH is unknown, and the INTO-HLH Registry will try to address this knowledge gap.

IMMUNE-ACTIVATING THERAPIES- CYTOKINE RELEASE SYNDROME

The HLH syndrome develops in some patients receiving treatments that activate their own immune system to fight their cancer. In this context, this syndrome is usually referred to as cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

The INTO-HLH Registry will gather data to understand how to control the cytokine storm without decreasing the effectiveness of these treatments.

Diagnosis

HLH can be difficult to diagnose. It can also be mistaken for other conditions such as viral infection, sepsis, or cancer. As a result, many people may see multiple doctors before the disease is identified. To help diagnose HLH, doctors will work to rule out infections, malignancies, or other conditions that could be causing similar symptoms and may order genetic and specialized immune testing to find out more.

If your doctor decides that genetic testing is appropriate for you or your loved one, tests can include targeted individual gene sequencing, HLH gene panel testing, and clinical whole-exome sequencing (WES). These tests can help determine if you or your child have certain gene mutations that may contribute to a primary HLH diagnosis. However, it can take several weeks before the results of a genetic test are available. Meanwhile, managing inflammatory signs and symptoms like fever, rashes, stomach problems, spleen enlargement, and others, is very important. Therefore, your doctor may also start treatment before genetic testing results are available to help manage symptoms.

SPECIFIC CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS

Generally, if a person meets 5 out of the 8 medical criteria below, doctors may consider a diagnosis of HLH. These criteria include:

- Fever

- Enlarged spleen

- Lower numbers of mature blood cells (cytopenias)

- An elevated level of triglycerides and/or decreased level of a clotting protein (fibrinogen) in the bloodstream

- Hemophagocytosis in the spleen, bone marrow, or lymph nodes

- Low or absent natural killer cell function, or similar immune measurements

- Elevated ferritin levels

- Elevated soluble CD25 level

Another tool to aid in diagnosing the non-genetic form of the disease is the HScore for Reactive Hemophagocytic Syndrome. Additionally, there are diagnostic tools for disease-specific contexts (such as macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile arthritis).

The treatment included in the HLH-94/2004 research protocol and targeted therapies is intended to suppress the inflammatory process of HLH so that a patient can receive a bone marrow transplant (BMT). If a patient has an underlying genetic or immune abnormality, then BMT is necessary for a long-term cure because HLH would otherwise keep reccurring. Historically, outcomes with BMT have been difficult for patients with HLH, and are now improving.

Long-term follow-up of survivors of transplants for HLH indicates that most children return to a normal or near-normal quality of life. The transplantation results are generally better when performed at a major pediatric transplant center where the doctors are familiar with this disease. Early and accurate diagnosis is essential.

Patients with the rheumatologic form of the disease (also known as MAS, Macrophage Activation Syndrome) are usually treated with steroids and targeted therapy. In addition, a small portion of these patients are treated with etoposide and steroids, and even BMT.

HLH associated with malignancies is a major therapeutic challenge as there is not enough evidence or a strong consensus about the appropriate treatment. The common approach is to control the cytokine storm with steroids or etoposide to enable malignancy-specific therapy. Either way, these patients suffer from poor survival, and improved therapeutic strategies are needed.

Lastly, patients with HLH/cytokine storms triggered by immune-activating therapies (usually given to treat a known cancer) are usually treated with cytokine-blocking treatment to preserve the anti-cancer effect.

INTO-HLH will hopefully improve understanding of the different subtypes and mechanisms causing HLH and improve therapeutic outcomes for future patients.

Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118(15):4041–4052.

Henter JI, Elinder G, Soder O, Ost A. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80(4):428–435.

Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al. Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2007;86(1):58–65.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503–1516. 6. Parikh SA, Kapoor P, Letendre L, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(4):484–492.

Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Blood. 2004;104(3):735–743.

Locatelli F, et al., N Engl J Med. 2020:382(19):1811-1822

Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(11): e27929.

Lehmberg K, Nichols KE, Henter JI, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocyto¬sis associated with malignancies. Haematologica. 2015;100(8):997–1004.

Ehl S, Astigarraga I, von Bahr Greenwood T, et al. Recommendations for the Use of Etoposide-Based Therapy and Bone Marrow Transplantation for the Treatment of HLH: Consensus Statements by the HLH Steering Committee of the Histiocyte Society. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1508–1517.

Broglie L, Pommert L, Rao S, et al. Ruxolitinib for treatment of refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood Adv. 2017;1(19):1533–1536.